Vapor Pressure of a Pure Liquid

Author: J. M. McCormick

Last Update: Fevruary 1, 2013

Introduction

In this exercise you will determine the enthalpy of vaporization (ΔvapH) of water, and the effect of a non-electrolyte solute (sucrose) has on water’s vapor pressure and ΔvapH. You are responsible for performing a literature search to find out more information on this system and why any change in the solute’s vapor pressure or ΔvapH might be important. This information must be incorporated into your formal report’s introduction.

Procedure

The procedure that you will follow is based on a literature procedure.1 However, the apparatus that you will use has been modified significantly. CAUTION! This exercise requires you to work with moderately high vacuums and calls for you to heat a closed system. Read the instructions carefully and familiarize yourself with the experimental set-up and methods before coming to the laboratory.

The apparatus that you will be using is shown schematically in Fig. 1. It consists of a manifold that will be used to control the pressure in the system, a calibrated Vernier gas pressure sensor (click here to review operation of the LabPro and the LoggerPro software that controls it) for measuring the pressure and a McLeod gauge and the laboratory’s mercury barometer, which will be used to calibrate the pressure sensor. The system itself consists only of a simple distillation apparatus.

Figure 1. Schematic diagram of the apparatus for the determination of the vapor pressure of a liquid sample by the boiling point method.

Figure 1. Schematic diagram of the apparatus for the determination of the vapor pressure of a liquid sample by the boiling point method.

The kit for this exercise includes the items listed in Table 1. Please check that everything is present and in good condition before beginning.

| Number | Item |

|---|---|

| 1 | 100 ml 19/22 One-neck round bottom flask |

| 1 | 19/22 Condenser |

| 1 | 19/22 Gas inlet adapter |

| 1 | 19/22 Claisen adapter |

| 1 | 19/22 Thermometer adapter (with o-ring) |

| 4 | Blue (19/22) Keck clips |

| 1 | Vernier pressure probe |

| 1 | Vernier temperature probe |

| 1 | Vial of boiling chips |

Table 1. Equipment needed for this exercise.

Upon coming to laboratory check that the manifold, McLeod gauge and ballast bulb have already been assembled and make sure all valves on the manifold are closed. Do not over tighten the valves! Start the mechanical pump. It should gurgle momentarily and then become silent. If it does not, then one or more valves have been left open; check that they are all closed. Under no circumstances is the valve to the pump be left open while the system is open to the atmosphere and the pump is running. If closing the valves does not solve the problem, shut down the system and consult your instructor.

Plug the fitting for the pressure sensor with a serum stopper being careful to completely cover the fitting. Slowly open the valve to the pump (the pump should make a gurgling noise) and then open it to approximately two-thirds full. Within a minute or two the pump should grow quiet as the air is removed from the line and ballast bulb; if it does not then there is a leak somewhere that must be sealed (most likely at the septum stopper). Once the air has been removed from the system, check that the McLeod gauge is in a horizontal position with the arm with the attached plastic scale is on top. Carefully open the manifold valve leading to the McLeod gauge; a little at first, and then fully open. The pump may gurgle at first, but should soon stop. Pump out the McLeod gauge for at least 10 to 15 minutes, during which time you can assemble the distillation apparatus. Once the McLeod gauge has been evacuated, close its valve on the manifold. The McLeod gauge must be left under vacuum at all times for it to function properly. Therefore, do not open the valve again when the system is not under vacuum. Close the pump’s manifold valve and open the vent valve. When the system has returned to ambient pressure, remove the stopper and install the pressure sensor.

The LoggerPro software should automatically recognize the sensor and display the ambient pressure. If necessary, change the units to mm Hg. You will be performing a two-point calibration of the pressure sensor, one at ambient pressure and one at the pump’s maximum pumping capability (~3 mm Hg). Record the ambient pressure in mm Hg from the laboratory barometer and correct the pressure using the equation posted by the barometer.2 Start the calibration routine in LoggerPro and enter the ambient pressure as the first calibration point (note that the vent valve must be open). Close the vent valve and open the pump valve (slowly at first and then fully open). The pump should gurgle at first and then become quiet while the pressure/voltage reading on LoggerPro should drop. If this does not happen, check for leaks. Once the pump has become quiet and the reading on LoggerPro has stabilized, carefully open the valve to the McLeod gauge. Wait a few minutes and slowly and carefully turn the gauge in a counterclockwise direction until it is in a vertical position. CAUTION! All movements of the McLeod gauge must be done slowly in the direction indicated using two hands to stabilize the gauge as it is turned. Rapid movement can break the gauge leading to a mercury spill. Be sure that the top black line on the scale is even with top of the left tube and read the pressure from the height of the mercury column. If this isn’t about 3 mm Hg, or less, carefully turn the gauge in a clockwise direction back to the horizontal position and continue pumping. If the pressure is in the correct range, enter the pressure reading from the McLeod gauge as the second calibration point to finish the calibration. Return the gauge to the horizontal position by turning it clockwise and close the valves to the McLeod gauge and the vacuum pump. Vent the system. The pressure reading displayed by LoggerPro should return to ambient pressure. If it does not, you may repeat the calibration procedure until it does.

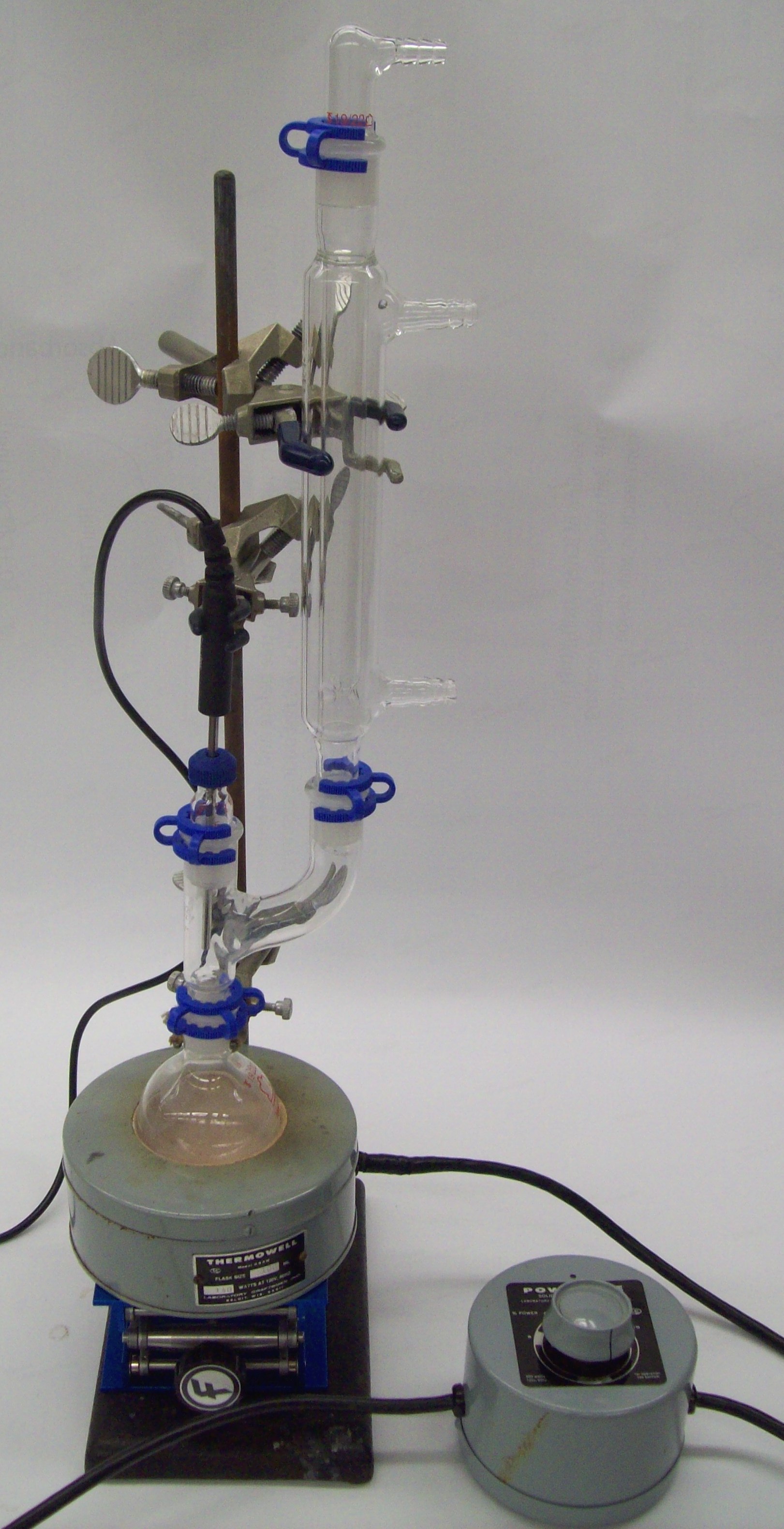

Assemble the distillation apparatus as shown in Fig. 2. Be sure to make all hose connections to the distillation apparatus before clamping it in place and do not forget to grease the ground glass joints with a small amount of high-vacuum silicone grease. You are advised to use the Keck clips to hold the joints together. It is recommended that two clamps (one on the neck of the round bottom flask and one on the condenser) be used to hold the apparatus in place.

To insert the temperature probe first place the inlet adapter into the Claisen adapter. Unscrew the blue retaining ring from the inlet adapter and slip the retaining ring and then the o-ring on to the probe. Carefully place the probe into the inlet adapter and turn the retaining ring until it just engages. Adjust the height of the temperature probe such that the bottom of the probe is level with the bottom of the Claisen adapter’s arm. Use a small clamp to hold the probe in a vertical position so that it does not touch the sides. Carefully tighten the retaining ring. Do NOT over tighten!

Figure 2. Distillation apparatus to be used in the determination of water’s vapor pressure. Note that the red vacuum hose that connects the gas inlet adapter (at the top of the assembly) and the condenser’s hoses for the cooling water have been omitted for clarity. The hoses must be attached to their respective glass pieces before the distillation apparatus is assembled.

Figure 2. Distillation apparatus to be used in the determination of water’s vapor pressure. Note that the red vacuum hose that connects the gas inlet adapter (at the top of the assembly) and the condenser’s hoses for the cooling water have been omitted for clarity. The hoses must be attached to their respective glass pieces before the distillation apparatus is assembled.

There are several heating mantles that will accommodate a 100 ml round bottom flask without sand or glass wool as packing material; use one of these. Do NOT plug the heating mantle directly into a wall outlet; plug the heating mantle into a Powermite (Fig. 2) and then plug the Powermite into the outlet. Note how the heating mantle is positioned on a lab jack so that it may be easily removed to stop heating the flask.

Don’t forget to add boiling stones to the carbonate-free deionized (18 MΩ) water and to start the cooling water flow.

As you will be using the LoggerPro temperature probe to record the temperature, it will need to be calibrated at three points (0 °C, room temperature, and 100 °C are convenient). Helpful hint: the calibration of the temperature probe can be done while the apparatus is being assembled or when you are waiting for the system to be evacuated.

When you are ready to make a run, close the vent valve, and open the valve to the distillation apparatus. Slowly open the valve to the pump and evacuate the system to the desired pressure (take care that the sample does not start to boil) and then close the valve. You are advised to start at low pressures first and record the boiling point as a function of ascending pressure. With the Powermite on a low setting, initiate boiling (a steady boiling, without bumping). You want the water to condense on the temperature probe and drip back into the round bottom, but not to condense much higher in the apparatus. When the temperature and pressure have stabilized record both.

Open the vent valve slightly to raise the pressure and then close it (the pump valve is closed and will remain closed until ambient pressure is again reached). During this operation boiling should cease. Continue heating until boiling starts again (the temperature and pressure should again stabilize). Repeat until ambient pressure is reached.

To collect data with decreasing pressures, first drop the heating mantle and cool the sample flask in an ice bath. Close the vent valve, if it is open, and then open the pump valve. Decrease the pressure in the system and then close the pump valve. Return the heating mantle to the flask and gently heat to boiling, as described above. Data for subsequent lower pressures is obtained in the same way (cooling the flask, decreasing the pressure and then heating again to boiling).

When you are finished, close the pump valve and open the vent valve to return the system to ambient pressure (the valve to the distillation apparatus should be open at this point). Turn off the pump and open the pump valve on the manifold to vent the pump. Disassemble the distillation apparatus. Don’t forget to remove the grease from the joints with a paper towel soaked in a little acetone and to dry all the glassware before returning it to the storage box. Remove the pressure and temperature sensors and place them in the storage box. Leave the vent, pump and system valves on the manifold open (the valve to the McLeod gauge must be closed).

To study the effect that the non-electrolyte sucrose has on the vapor pressure (and ΔvapH), you need only repeat the measurement with a sucrose solution instead of pure water.

Results and Discussion

The effect of temperature, T, and pressure, p, on equilibrium between a pure liquid and its vapor at its boiling may be described using the Clapeyron equation (Eqn 1.) where ΔvapS and ΔvapV are respectively the molar entropy change and the change in the molar volume associated with the liquid to vapor phase transition.1,3

| |

(1) |

A number of approximations can be made to simplify this equation even further. First, we may use ![]() , where ΔvapH is the molar enthalpy change for the vaporization, because the two phases are in equilibrium (ΔvapG = 0) at some constant pressure and temperature. We may approximate ΔvapV as simply the volume of the gas, Vg, because the volume of gas will be much larger than that of the liquid. And finally using derivative relationships, we may then write the Clapeyron equation as Eqn. 2.

, where ΔvapH is the molar enthalpy change for the vaporization, because the two phases are in equilibrium (ΔvapG = 0) at some constant pressure and temperature. We may approximate ΔvapV as simply the volume of the gas, Vg, because the volume of gas will be much larger than that of the liquid. And finally using derivative relationships, we may then write the Clapeyron equation as Eqn. 2.

| |

(2) |

This is still not a particularly useful equation because the derivative depends on temperature. However, if we substitute in the compression factor, Z, in the form ![]() , we can remove the apparent temperature dependence to give Eqn. 3.

, we can remove the apparent temperature dependence to give Eqn. 3.

| |

(3) |

If the gas behaves ideally (Z ≈ 1) then a graph of ln p as a function of 1/T would be a straight line with a slope of -ΔvapH. For real gases, however, Z itself will decrease with increasing temperature, which should give some degree of curvature to the graph at high temperatures. For water Z = 0.986 at 100 °C,1 which means water may reasonably treated as an idea gas, even at its boiling point.

Another problem with this method is that ΔvapH is also temperature-dependent. The change in ΔvapH at two different temperatures may be written as Eqn. 4, where ΔCp is the change in the molar constant pressure heat capacity for the vaporization (i. e., Cp(vapor) – Cp(liquid)). If we have data on the constant pressure heat capacity of both the vapor and the liquid over the temperature range of interest, we can evaluate the integral in Eqn. 4. However, if we do not have such data we can use the average of ΔCp over the range. If the change in ΔvapH with temperature is appreciable over the temperature range under consideration we should observe curvature of a graph of ln p as a function of 1/T, just as if the vapor were behaving non-ideally. In practice, the graph of ln p as a function of 1/T for many liquids is nearly linear indicating that either the two effects are fairly small or that both are changing at approximately the same rate (and thus their ratio remains relatively constant).

| |

(4) |

From your data determine ΔvapH at 1 bar of pressure and 298.15 K both in the absence and presence of sucrose. In your Results section be sure to include the graph that you prepared to determine these values (one for water alone and one for the sucrose solution). Perform an error analysis to determine whether any differences are statistically significant. Does the presence of sucrose change ΔvapH for water? Does it change the vapor pressure at a constant temperature? Discuss your findings.

You can also fit your data to the Antoine equation, shown as Eqn. 5 where a, b and c are empirical parameters that are unique to a compound, T is the temperature (either in Celsius or Kelvin) and P is the pressure (usually in bar). Present a graph showing the data and the best fit line through the data. Compute a, b and c and their uncertainties at 95% confidence. Compare your results to those available on-line at NIST.

| |

(5) |

References

1. Garland, C. W.; Nibler, J. W. and Shoemaker, D. P. Experiments in Physical Chemistry, 7th Ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, 2003, p. 199-207.

2. Brombucher, W. G.; Johnson, D. P. and Cross, J. L. Mercury Barometers and Manometers, National Bureau of Standards Monograph 8; Washington, D. C., 1960.

3. Atkins, P. and de Paula, J. Physical Chemistry, 8th Ed.; W. H. Freeman: New York, 2006, p. 117-131.